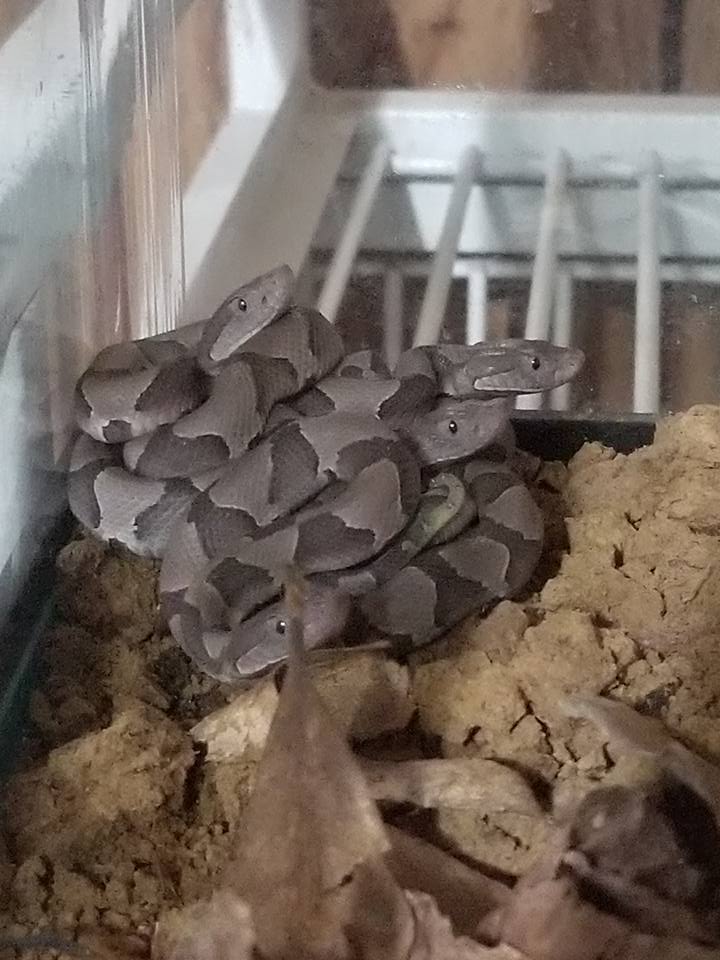

Cohabitation is a very controversial topic in the herp community and there does not seem to be one clear answer. Some people vehemently protest that housing multiple animals together is a risk without benefit and should never be done. Others seem to feel like it is rarely a big deal and advise not to worry about it. As with most things, the truth is somewhere in the middle, but knowing where to draw the line takes research and an intimate familiarity with the individual animals in question.

The risks of cohabitation include injury or death of the animals, subordinate animals being denied access to resources such as food and basking sites, and overall stress that can weaken the immune system and invite illnesses. The potential benefit held out by proponents of cohabitation is the possibility of the enrichment provided by having another animal to interact with. Although studies are scant in this area of natural history, we know that some species do socialize to different extents in the wild. This could mean that offering these interactions in captivity may be of psychological benefit. Regardless, cohabiting should not be done merely to save the expense or labor of maintaining multiple enclosures, and the decision to do so should be based on more than a pet store employee telling you that “they should be fine.”

Many or most species found in the pet trade make poor candidates for cohabitation, including any species known to eat other herps in the wild. Furthermore, there have been numerous observations of species that rarely interact in the wild developing problems with each other in captivity, particularly when there is competition for resources and during feeding times. It should also be noted that even among species that seem to interact safely under some circumstances, there are pairings that are best avoided. These include housing a single male and female together (often resulting in the female being pursued continuously and possibly bred too often), housing differently-sized animals together (larger specimens are much more likely to kill or injure smaller animals), housing two territorial males together (males of many species, such as anoles, are known to respond to presence of other males as an intrusion). Even herbivores may attack each other if they feel another animal is invading their space.

Although there are groupings that typically take place without issue (e.g., ribbonsnakes, many small frog and geckos, mixed species enclosures of similarly-sized insectivores, many aquatic turtles, etc.), mishaps can occur in any community. It is best to enter into any cohabitation very carefully and thoughtfully after diligent research. Managing communities requires attentive observation, and it is essential that excellent husbandry is being practiced to mitigate issues from competition. Especially if you have never kept herps before, it may be better to start by erring on the side of caution until you gain more experience or have the guidance of an accomplished keeper.